BY Leon Lazaroff

TheStreet

NEW YORK (TheStreet) - Brandon Rees, who helps oversee the AFL-CIO's pension fund investments, is trying to convince Tribune (TRBAA) to shelve any sale of its eight daily newspapers, which include The Los Angeles Times and The Chicago Tribune.

NEW YORK (TheStreet) - Brandon Rees, who helps oversee the AFL-CIO's pension fund investments, is trying to convince Tribune (TRBAA) to shelve any sale of its eight daily newspapers, which include The Los Angeles Times and The Chicago Tribune.

TheStreet

NEW YORK (TheStreet) - Brandon Rees, who helps oversee the AFL-CIO's pension fund investments, is trying to convince Tribune (TRBAA) to shelve any sale of its eight daily newspapers, which include The Los Angeles Times and The Chicago Tribune.

NEW YORK (TheStreet) - Brandon Rees, who helps oversee the AFL-CIO's pension fund investments, is trying to convince Tribune (TRBAA) to shelve any sale of its eight daily newspapers, which include The Los Angeles Times and The Chicago Tribune.  |

| David and Charles Koch |

Rees' lobbying was prompted by David and Charles Koch, the Tea

Party-funding multi-billionaire owners of the oil and chemicals

conglomerate Koch Industries, who have said they may bid for the

newspapers if Tribune decides to put them up for sale. Tribune, which

could owe as much as $225 million in back taxes, needs the cash.

Rees, the acting director of the AFL's Office of Investment, is

realistic about the situation. If Tribune wants to sell and the Koch

brothers want to buy, there are few humans on the planet capable of

outbidding them. Each of the Koch brothers has a personal fortune

totaling $43 billion, according to data compiled by Bloomberg,

while Koch Industries generates $115 billion in annual sales. The

brothers are the sixth and seventh wealthiest people in the world.

The Kochs have also been among the country's largest funders of

groups that seek to undercut public pension fund benefits and curtail

collective bargaining by municipal unions. Labor unions, as well as

groups urging steps to combat global warming, another Koch foe, are

loath to see these dailies become a unit of one of the world's largest

fossil fuel providers.

Regardless of the overall decline in circulation, the papers

remain major institutions in their home regions. They include the

largest dailies in Illinois, California, Maryland (The Baltimore Sun) and Connecticut (Hartford Courant) as well as two in the politically-charged state of Florida (Orlando Sentinel and South Florida Sun-Sentinel of Fort Lauderdale), and also the national Spanish-language daily Hoy.

Ironically, the sale could be an immediate gain for some of the

union federation's members. That's because billions of dollars in

members' pension fund monies are managed by L.A.-based Oaktree Capital

Management, the world's largest distressed debt investor, which owns a

23% stake in Tribune, making it the media company's largest shareholder.

Rees argues that selling now, even at a profit, would shortchange

union members. Tribune's newspapers, which exited a messy and

debilitating four-year bankruptcy in December, are beginning to show

improvement as Oaktree President Bruce Karsh, who doubles as Tribune's

chairman, said in a letter last month to national and California labor

leaders. Tribune's "publishing assets are performing ahead of plan thus

far this year" said Karsh, adding that a sale is only one option the

company is considering.

Nonetheless, Rees is pressing Tribune to hold off on an auction for

its newspapers, valued in the company's 2012 reorganization plan at $623

million.

"Oaktree as short-term investors may want this transaction

now whereas their clients, the pension plans, are longer-term investors

who may benefit from continued ownership of these newspapers as they

continue to adjust to market realities," Rees said in an interview on

Thursday. "If the Kochs, who are certainly smart investors, were to be

buyers here, that demonstrates there's still value to these media

properties. From our standpoint, there may be greater profits to be had

later on."

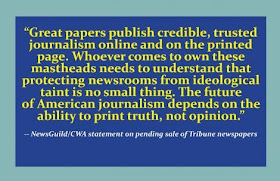

At a gathering Wednesday in Washington hosted by the

Communications Workers of America-Newspaper Guild, union activists and

critics of media consolidation stopped short of painting a

sky-is-falling picture were the Koch brothers to buy Tribune's

newspapers. Guild President Bernie Lunzer said he's refraining from Koch

bashing, adding that there may even be opportunities to organize

workers at these newspapers. (Currently, the Baltimore Sun is the only Tribune newspaper represented by the Guild.)

Read more at: http://www.thestreet.com/story/11964451/2/afl-cio-wary-of-koch-money-presses-tribune-to-shelve-newspaper-sale.html